A Salmon Journey

From the Shuswap, to the Ocean, and back again.

Follow the journey and life of a Sockeye Salmon.

In the fall, my mother lays me and I begin my life as an egg in the fast-flowing Adams River.

My egg is laid with 2,200 to 4,300 sibling eggs in the Adams River.

Through the fall and into winter, I grow inside my little egg home until I'm big and developed enough to break out and swim free. I'm now called an "alevin".

I hatch in the Adams River with about 900 siblings.

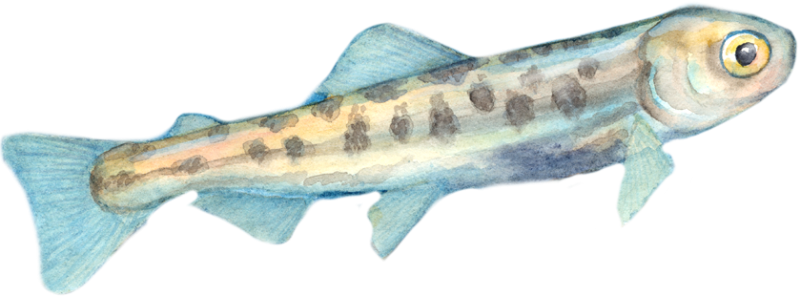

When spring begins in March, my siblings and I come out of our gravel homes and venture into the world. We're now called "fry".

We swim straight to the Shuswap Lakes at night.

I grow bigger and stronger.

I hang out in the Shuswap Lake for 1 year.

Before long, I'm too big for the Shuswap Lake and need to continue on.

By the time I leave the Shuswap, I only have 250 siblings.

My journey to the ocean is the most dangerous I've ever experienced in my young life.

It takes me 1 week to swim to the ocean.

I spend my time swimming around where my predators are killer whales & human fisherman.

I spend 2 to 3 years in the ocean, growing and avoiding predators.

In the open ocean, I have plenty of food to help me grow.

I grow a lot while I'm in the ocean.

In early September I begin my return home.

I stop eating. I now only have 9 siblings.

The journey home is very dangerous and I swim hard.

I encounter many hazards on my journey home.

I travel through the fish ladders at Hell’s Gate on the Fraser River.

We travel very far.

Our journey takes us from the Pacific Ocean, through the Fraser and Thompson Rivers, and finally into the Adams River.

Finally, after weeks of hard work, we've finally made it back home to have our babies.

I reach the Adams River with only 1 sibling from 4 years ago.

Just like my parents died for me, I leave my body for my babies, eagles, gulls, bears, and other animals. It's the cycle of life.

I die and leave my body for food.

Special Thanks

We would like to offer a special thanks to Brenda Guiled for the use of her wonderful illustrations and adapation of her book, Sockeye Salmon Odyssey: The story of sockeye salmon of British Columbia through their lifecycle and travels.

My egg is laid with 2,200 to 4,300 sibling eggs in the Adams River.

My egg looks like an orange-red marble and has no markings; it's soft and squishy. My egg is about the same size and colour as a huckleberry.

Inside, I'm just a tiny speck of new life. I float in a 'soup' of all the nutrients I need to grow into a baby sockeye.

My egg needs a good home in the stream. Cold, rushing water helps me breathe properly and keeps my egg clean. If the current carries my egg to muddy places or quiet backwaters, I could suffocate and die.

Throughout the winter, streams sometimes run dry or freeze, which kills my siblings' eggs.

From each big bunch of eggs, thousands of my siblings don't survive. But for those of us lucky enough to survive, we begin life in a safe, healthy part of the stream. We start to grow - and fast.

I hatch in the Adams River with about 900 siblings.

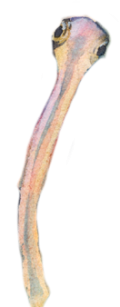

I become an alevin in about three months if the water is the right temperature - very chilly to humans! If the water is icy cold, it can take up to six months to hatch. Whether we hatch in three months or six, we swim free in the coldest time of year.

I'm not safe yet, though. Fast-running water could carry me away. I could dry out or freeze to death. But now I can do something about these dangers because I can swim!

I know, somehow, to wiggle down into the gravel into safe little holes and caves.

But what will I eat? Luckily, my lunch (called a yolk sac) is hooked right into my tummy. It'll feed me until spring.

We swim straight to the Shuswap Lakes at night.

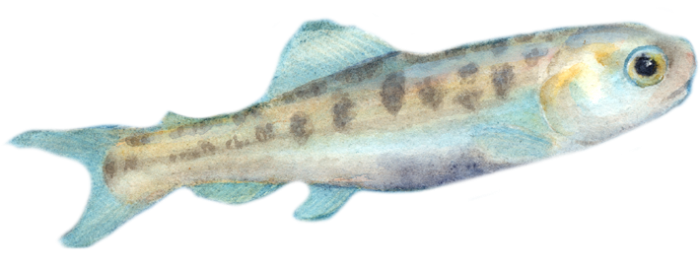

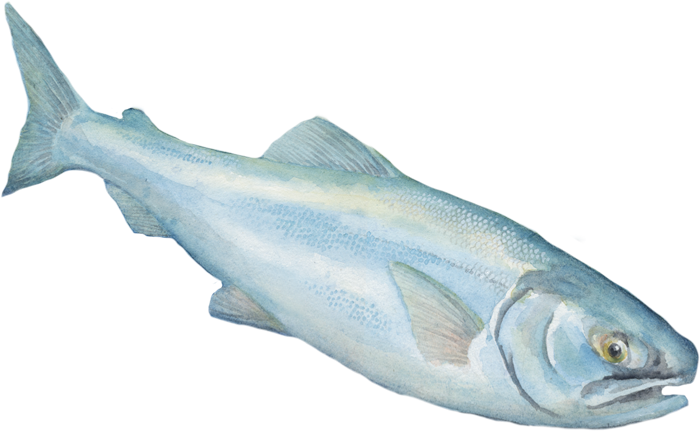

I am now 6-8 cm long and silvery in colour. I have darker patches on my side and back called "parr marks".

My yolk sac is used up but my food is now available in the warming waters. I eat plankton, which are about the size of a pinhead. The plankton eat tiny pieces of dead salmon, who in turn are eaten by larger plankton and insects. In this way, my family provides for us.

For a few weeks, I stay near where I was born. Soon though, I need more food and a safer place to live than the stream can provide. I could hide better in the weeds and deeper water of a lake.

How will I find a lake, though? My parents, as fry, knew how to do this. So did my grandparents and all of my ancestors, going back thousands of years.

Humans say that we smell our way to the lake, but it's a bit more complicated than that. We use our lateral lines, which are a string of holes along the side of our bodies. Through my lateral lines, I can sense changes and objects in the water.

I hang out in the Shuswap Lakes for up to 1 year.

I grow and change so much in the lake that I'm now called "parr". I still have my finger markings for camouflage; my markings make it easier for me to hide in the ripples and shadows of the lake.

Why are we called par? About 300 years ago, people in Scotland thought "parr" was a good word for little trout with similar markings. No one knows why - they never wrote it down.

As I grow to the length of a child's hand, my back and sides become much more silvery. I'm now called a "smolt" because of my colouring.

I spend a couple years growing bigger and stronger in the Shuswap Lake. I'm preparing for my next adventure.

By the time I leave the Shuswap, I only have 250 siblings.

I journey to the ocean for the same reason I went to the lake as a fry. I need more food and a safer home.

It's a dangerous trip, but my siblings and I are ready. Sadly, we won't all make it.

It takes me 1 week to swim to the ocean.

My siblings and other family members from hundreds of other rivers travel to reach the ocean. Some of us only have a short distance to go; others travel for over 1,000 km!

I travel to Kamloops where the North and South Thompson rivers meet. I meet many other family members here. About halfway between Kamloops and Vancouver, the Fraser River squeezes through a steep canyon called Hell's Gate. This will be a difficult area to to navigate when I return. About 450 of my siblings have made it this far with me.

Once I'm near the ocean, I enter an estuary. I stay with my family in tight groups, called schools, for safety. About 200 of my siblings die in the estuary.

After staying for a few days, or sometimes weeks, in the estuary and moving up and down from fresher to salty water, I head to the great, wide ocean.

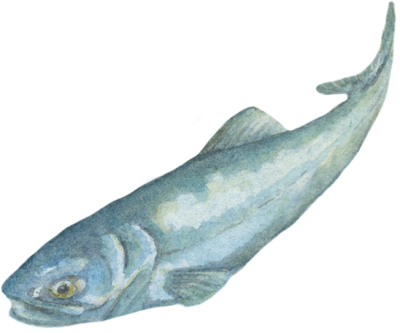

I spend 2 to 3 years in the ocean, growing and avoiding predators.

The islands on the BC coast create very complicated waterways for me to swim through. There are millions of islands I must navigate, as well as plenty of predators.

Some of my predators are the many animals that live on and around the islands who think I would make a nice meal.

Sea lice are also a concern because they can quickly kill us while we're still small.

Some of my scariest predators are sharks, tuna, seals, dolphins, and whales. Some of them can swallow many of us in one gulp!

I also have to watch out for humans, who use lines or big nets to catch us. Even if I manage to avoid the nets, I need to be careful not to get tangled in abandoned nets and garbage.

I grow a lot while I'm in the ocean.

My remaining siblings and I gain about 2 to 7 kilograms of weight during the 2 to 3 years we spend in the ocean. I grow to about 3.6 kilograms.

I mostly eat krill or small crustaceans in the ocean. Luckily for me, there are umpteen-gazillion krill in every part of the ocean! Some whales even grow huge by only eating krill. The orange-red colour in krill makes my muscles change colour - my flesh is now red. Sockeye flesh is the reddest of all salmon because we eat the most red krill, which thrives in the middle of the ocean.

Unfortunetly, plastic and Styrofoam also break down into tiny pieces and look just like my favourite food. They fill our tummies and block our guts, which makes us starve to death.

I stay together with my siblings and cousins until I'm about four years old, when we return to our home rivers.

In early September I begin my return home.

After living in the ocean for two years, I'm now a full-grown adult sockeye. My brothers are a little larger than my sisters, but we all look very similar. We're silvery, sleek, and strong. I have lots of oil and fat in my body which will nourish me on my journey home.

I've lived in the deep ocean for most of my adult life, but now I return to the mouth of the river that I left when I was a smolt. However, I'm not used to the fresh water and stay in the estuary while my kidneys get used to the change. They're now working to keep salt in my body, instead of getting rid of it like in the ocean. This only takes a few days.

Once my body has acclimatized to the fresh water and the river is deep and cool enough, I start swimming upstream with my siblings and cousins.

As I swim upstream, my skin changes colour. I know I must return home to have my babies. My brothers drastically change shape, becoming much larger than my sisters. My sisters have two egg sacs that make up about 25% of their entire weight.

I encounter many hazards on my journey home.

We swim against the current and through rapids, which is a lot of work. It's very easy to get tumbled around and pushed into rocks.

We swim together and try to keep to the edges of the river, in eddies where the water slows down in pools and swirls. When rapids rush across the entire river, we need a lot of energy to fight and jump upstream.

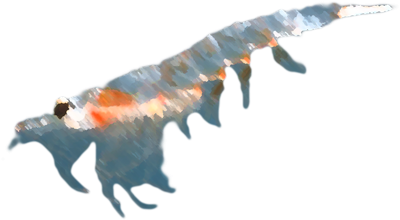

Just like when we traveled to the ocean, many animals try to catch us for their dinner. Bears love to try to catch us.

I travel through the fish ladders at Hell’s Gate on the Fraser River.

For the second time in my life, I travel through Hell's Gate Canyon. This time, though, I have to swim against the rushing current. I stay near the eddy line and find my way to the fishways to make it past this obstacle.

I reach the Adams River with only 1 sibling from 4 years ago.

We're now ready to have our babies.

My female cousins dig up gravel from the stream bed and flip away small rocks with their tails; they're making a nest (also called a redd) for their eggs. It's not too big, just enough so that the current doesn't carry away their eggs. They lay dozens of eggs in one redd, then move upstream and repeat the process. The gravel they flip out of the new redd helps cover the last one.

My cousins lay her thousands of eggs along the stream this way. Some eggs are in better spots than others. My male cousins line up closely to females who have just laid eggs so they can release their sperm over the new eggs.

This should be easy, but my male cousins are all trying to do the same thing and sometimes fight with one another. They use their size and strength plus their kypes (hooked noses) and sharp teeth. They bite and hit one another, hurting both their rivals and themselves. We can be hurt very easily now.

When our sperm and egg combine, a magical new life begins; it's the beginning of a baby sockeye.

I die and leave my body for food.

For 10 days, we try to stay close to our eggs to protect them. If we're not killed and eaten, we finally become so weak and worn out that we die.

Our bodies fall apart and rot. Our flesh and bones become good food for all kinds of other small plants and animals. These living things, in turn, grow into fresh food for our babies to eat after they've hatched and become fry.

And when the salmon-eating animals die, their bodies become meals for new life, too.

It's all a great cycle of life, and every part of it matters to every other part. Because sockeye and other salmon connect the ocean to rivers and lakes, we are especially important to all the living things in both places.

And that includes humans. If you keep us salmon healthy and strong in our ocean and freshwater homes, then many things in the world that you love and need will stay healthy and strong.